Back in grade school, did you ever have a class where you aced every test and answered all the questions right, and then the following year, you had a teacher and a classroom where everyone else seemed to understand what was going on, but you didn’t have a clue?

Or have you ever seen a group of talented musicians come together to create an unlistenable, screechy album?

These sorts of things happen all the time. They suggest that factors such as environment, structure, collaboration and leadership can be game changers.

Yet it’s difficult to see how an organization might be getting in the way of its own success. Maybe you have a disorganized system where the new hires get assigned to the high-tier clients. Or you have a talented team, but the projects tend to flop due to bickering and infighting.

Phrases like “empowering a team” and “unleashing potential” sound elusive, like one of those water snakes that slip through your fingers when you try to grasp it. But really, there are concrete ways to build an effective team. As it turns out, capacity, design and structure have as much to do with team effectiveness as anything else.

Are you interested in learning some of the secrets to building a high-power team? About the optimal way to design your team for the output you’re looking for, and those things to avoid?

In this post, we’re going to look at powerful tools for designing a team structure that manages itself and delivers results, and at organizational principles and designs to build an effective team that works for you.

A Team Versus a Group: Definitions

Teams aren’t necessarily people who work together in the same space and who perform the same tasks. Let’s get down to the basics first off and clarify just what is meant by a team versus a group.

A group, loosely defined, means two or more people who have significant things in common. However, a group may or may not function as a team. Here’s an example to illustrate this point. A group of people boards a ship to take a cruise, but a team of people devises a plan when the ship starts to sink.

This example clarifies the key distinction between a group and a team. Although a group has significant things in common, a team works toward a common goal.

Scott Tannenbaum and Eduardo Salas, authors of Teams that Work, the Seven Drivers of Team Effectiveness have outlined five characteristics of a team.

- A team must consist of two or more people. Nobody working solo is on a team.

- Team members interact continually (though not necessarily daily).

- The people within the group see themselves as a unit (but not exclusive to other teams).

- The members of the group are aligned around the same purpose, and work toward the same goal.

- Members of the team have roles and separate duties. They rely on one another’s skills to achieve goals.

Teams can be remote, where the members never see each other in real life, or in-person, where the members work alongside each other every day. Oftentimes teams are formal, with assigned roles, and are designed to last for some time. This isn’t a requirement, however. Some teams casually band for the space of a few hours, then disband once the purpose is achieved.

Teams function in every aspect of life, to solve all sorts of problems and work toward a variety of shared purposes.

A basketball team seeks to score more baskets than the opposing team, and a tennis team to score more points than the players on the other side of the net. A flight crew seeks to safely and comfortably bring its passengers to the destination, and a restaurant staff to deliver hot meals with a smile. A software team collaborates to build a product that solves the client’s problems. SWAT teams work to mitigate a crisis, and military units to safeguard the common good.

In a variety of capacities, we’ll all experience being part of a team. And as we all can attest, it certainly isn’t always easy.

However, a team provides many benefits above and beyond those of a group. Teams generate synergy, a capacity to solve problems and achieve goals that wouldn’t be possible within a group where everyone works in silo. Competition is minimized in a high-functioning team. Everyone shares best practices and the environment generates camaraderie and innovation.

This highlights another key distinction between groups and teams. A group evaluates people individually, it rewards individual performances. A team, on the other hand, evaluates everyone as a unit. It measures performance based on the group.

As we’ll discuss more in this post, a team’s success is in large part determined by its design. A poorly designed team gets in the way of its own objectives, while a carefully crafted team leverages all its potential. As Naomi Stanford writes in her book, A Guide to Organization Design, “Risk of failure can be completely avoided by consciously designing a new organization or redesigning an existing one in such a way that it performs well and adapts readily to changing circumstances.”

Characteristics of an Effective Team

Tannenbaum and Salas are both organizational psychologists who have studied teams for over thirty years, in industries ranging from health care to financial services to airline travel. Over this time, they have identified three characteristics of an effective team.

1. Manages Resources

An effective team understands the resources required to achieve an objective, and utilizes a resource management plan to get there.

Resources include everything from materials, to equipment, to facilities, to the skills and time of team members. Effective resource management includes procurement plans that ensure the prudent acquisition of materials, systems that facilitate work-life balance for each team member and resource leveling to distribute work sensibly throughout a project.

2. Works Through Challenges

An effective team isn’t one that never has hiccups, disagreements or failures. In fact, open and honest disagreements are a sign of a collaborative and healthy team. And any team that takes risks is sure to fail from time to time.

However, an effective team doesn’t lose its productive capacity in the midst of challenges. It functions within a culture that fosters psychological safety so that the people feel valued and respected in the midst of conflict or failure.

3. Adapts and Innovates

An effective team isn’t fixated on one goal. A quarterback, for example, isn’t afraid to call an audible at the line of scrimmage when he feels a different play is more likely to achieve a first down.

An adaptive mindset allows a team to back track or change course when that’s more likely to achieve the objective. It doesn’t hesitate to develop new skills, and realign its structure when necessary.

Tannenbaum and Salas have also identified the components of an effective team. Here are the “Seven Cs” that make up a team.

1. Capability

Although skill isn’t everything, it certainly is necessary for teamwork. A software team must be fluent in the language it’s going to use to build a product. A fishing team must understand how to weather a storm, drop anchor and navigate by the stars. A financial advisor knows the sales techniques to move products. Generally, skills are distributed within a team.

2. Coordination

The coordination of a team impacts productivity every bit as much as the capability of its individual team members. This point lies at the heart of this paper, in fact. Coordination is the reason for why some teams with seemingly mediocre skills flourish, while other teams with stellar skills fall flat. Poor coordination is one of the key causes of social loafing.

3. Communication

Have you ever been on a team where someone chimes in with a warning, and is completely ignored, then later, when it’s too late, the team realizes it should have heeded the counsel?

A healthy team is receptive to listening to all perspectives. It gets the right information to the right people at the right time. Fluid communication is facilitated by good communication tools, regular check-ins and a transparent culture that values individual contributions.

4. Coaching

Even the most autonomous team functions best with some supervision and leadership. Leadership sets the tone, reinforces the culture in the team, boosts momentum and aligns a team around goals.

5. Cooperation

Cooperation, fundamentally, is about trust and openness. It means people feel comfortable bringing their full selves to the team. Oftentimes cooperative teams generate a swarming effect where everyone works together on the same task to bring it completion.

6. Cognition

Cognition, according to Tannenbaum and Salas, means that teams have a mutuality or a similar approach. Organizations with strong cultures excel here, as people are more likely to have similar priorities and be incentivized for the same reasons.

7. Conditions

Every team works within a specific range of resources. Members have access to a certain amount of materials and equipment, work within a given facility or digital platform, and give a certain amount of time. These conditions in part influence and determine the team’s output.

Regardless of its structure or industry, every effective team carefully selects the proper conditions to cultivate success.

Four Teamwork Myths

We all have an idea in our head of how the ideal team functions and behaves. Maybe it includes team members laughing with each other during rapport building activities, slapping each other on the back and going out for beers together after work.

Although this description may characterize an effective team, these attributes aren’t fundamental. Let’s bust up some commonly held notions about what a team must be.

1. A Team Needs the Best and the Brightest

We’ve seen sports teams composed of seemingly mediocre athletes who win championships, and teams with star players who don’t even make it to the playoffs.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, skill isn’t the most important criteria for a great team member. Emotional intelligence matters every bit as much, and sometimes more, than skills. Characteristics like attitude, humility and a willingness to learn also impact an individual’s contribution to a team.

2. High-Functioning Teams Communicate Every Single Day

The widely-propagated agile principle promotes face-to-face communication and a daily scrum meeting. It has set an expectation that a team must be in constant communication, or else things go off the rails.

However, a team’s structure determines its ideal communication patterns. In some designs, requiring every member to communicate with every other member is simply excess and wasted energy.

3. Teams Produce More Together Than They Would Individually

Although teams possess the capacity to create a “one plus one equals three” phenomenon, this doesn’t occur automatically.

The synergy of a team must be cultivated. If it isn’t, then the opposite may occur instead. Sometimes when a group coalesces into a team, a phenomenon called social loafing occurs, where people produce far less than they might if they were working on their own. Some studies have shown that in group settings, individual output decreases by as much as one half.

4. Large Teams Are Bad

In this day of agile, any team over six or seven members is seen as an anathema, as though it’s asking for failure. This simply isn’t so. The size of the team is determined by the project at hand.

Sometimes the best criteria for team success is how long its members have worked together. Teams become the most productive after it’s gone through the storming and forming phases, and each understands his or her role. Strong central leadership can eliminate some of the infighting and conflicting priorities that take place within a large group.

Although there’s no one right way to build a team, certain conditions almost always preclude growth. Now that we’ve busted up a few teamwork myths, let’s look into why team structure matters.

Conway’s Law: Why Team Structure Matters

In 1968, the computer magazine Datamation published a research paper from Melvin Conway, a computer programmer, scientist and doctor of mathematics. The Harvard Business Review had already rejected the paper. And Conway buried the thesis at the very end.

Pithy insights have a way of surfacing eventually, however. Seven years later Frederick Brook featured Conway’s thesis in his book of technology essays, Mythical Man-Month, using the moniker “Conway’s Law.” The principle gained traction, and today this law is widely applied not only in software companies, but in the design of organizations in general.

Conway’s Law Defined

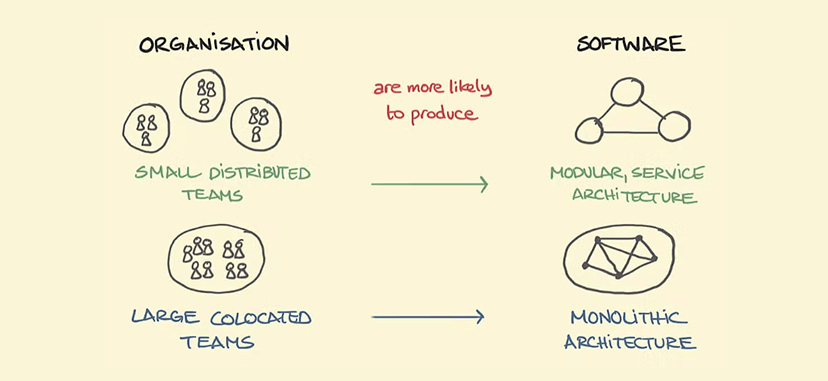

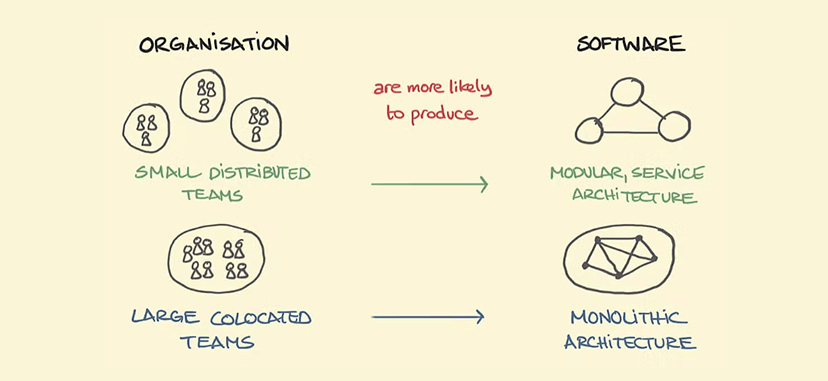

Conway’s Law essentially states that the structure of software mirrors the structure of the team that built it. More broadly, the product, output or service of an organization is reflected in the communication structure of the team that creates or provides it.

As Conway himself explains: “Organization which design systems…are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations…the very act of organizing a design team means that certain design decisions have already been made, explicitly or otherwise”

Examples of Conway’s Law

As an example, take the companies Chevy and Tesla, and more specifically the cooling systems built into the automobiles of each. Tesla uses a simple organizational structure, and its engineers designed a car with one cooling system to handle the entire automobile.

Chevy, on the other hand, is a much larger company with a decentralized organization that assigns separate teams to specific components of the car. Its cooling system reflects this. A Chevy automobile has three cooling systems: one for the battery pack, one for the cabin, and one for the battery.

Conways Law is reflected in software design as well. A team of three software engineers who each know three different languages inevitably builds a system with a three-tiered architecture.

All this is to say, an organization with complex communication structures can’t create a simple product. An organization with many different teams, where each reports to a different VP who’s incentivized to reach a different goal, and where an individual on one team must interact with several people to communicate with a member of another team, creates a product that reflects this complexity.

As many leaders and project managers attest, there’s no getting around Conway’s Law. No matter how much it might want to, a team cannot build something counter to its design.

A Solution to Conway’s Law

Conway poses a solution to his principle: “Ways must be found to reward design managers for keeping their organization lean and flexible. There is a need for a philosophy of system design management which is not based on the assumption that adding manpower simply adds to productivity.”

This notion has come to be known as the Inverse Conway Maneuver. The maneuver is about creating a clear structure, and limiting the cognitive demands of individual team members on the team. Essentially, it means that if you want to create something that’s simple, or to provide fast, straightforward service, utilize a simple team design.

The Big Lesson from Conway’s Law

One overarching takeaway from Conway’s law is that a team cannot focus exclusively on what it wants to produce, be it a widget, a website, or a service experience. In order to achieve its goal, it must focus on the design of the organization as well.

And so when a team is stuck in a hairball of a mess, sometimes the solution is to simplify the team structure. As Conway emphasizes, this means that organizations must continually be open to re-design.

Conway’s Law convinces us that design matters with respect to team effectiveness. But what should this design look like? As it turns out, there’s many options. Some that work, and some that definitively do not.

Four Team Structures that Always Fail

Although there’s no one right way to structure or design a team, certain formulas just aren’t going to cut it at any time or anywhere. Let’s look at some of these.

1. Required Skills Nowhere to Be Found

As discussed earlier, capability is a key component to an effective team. Although at some level this is a no-brainer, sometimes it requires a little digging to identify required skills, and then classifying each individual’s skills on a spectrum.

Take, for example, an accounting firm that only has a few skilled members and many entry-level members. It’s quite possible that the team’s skill mix won’t correlate to what’s required by the clientele. A junior member who’s just cutting his teeth may be assigned to a top tier client outside of his skill range, and provide shoddy service.

A successful team clearly defines the skill levels required for the work at hand, then looks for suitable matches to create the team.

2. Work Performed in Silos

Sometimes roles and duties are so clearly defined that one team member can perform one task, then pass the work right onto the next team member. However, if the first person immediaely closes the books and moves onto other things, it opens the door to failure.

Take, for example, a restaurant where the cook prepares a meal, and the server delivers it to a patron. It’s quite possible that the patron may have changed his or her mind, or made a mistake in placing the order. Both the cook and the server need to be in constant communication with one another in order to correct this and provide satisfactory service.

As stated earlier, one fundamental characteristic of a team is that the members are dependent on each other.

It’s easy for this silo work pattern to occur in remote teams. One way to solve it is with solid communication systems.

3. Spiderweb Communication Networks

Oftentimes in a complicated team design, one person has to go through several channels just to speak to someone on another team. This forces things to proceed at a pace that’s slower than molasses in January. It may even mean that the effort to communicate does not take place at all. Yet fluid communication is imperative to a project’s success.

As discussed, Conway’s Law can’t be fought, rather it needs to be dealt with. The solution to a complex team design is to simplify structures as much as possible.

4. Teams Without Autonomy

Building strong rapport is central to a cooperative and productive team. And according to forensic psychologists Laurence and Emily Alison, authors of Rapport: the Four Ways to Read People, autonomy is a key to achieving this.

A top-down, command and control structure stifles teams. When team members are told what they can and cannot do with rigid specificity, it may well lead to high incidences of social loafing.

Granting a team the license to determine when it holds meetings and who receives which responsibilities means it’s more likely to go at things with a gusto.

In pretty much any scenario, a team that reflects any of these characteristics sets itself up for failure. Now let’s look into some options for team structures that really work.

Five Successful Team Structures

There’s no one right way to design a team. A right structure varies depending on the industry and the objectives of the organization. And each organization can succeed under a variety of structures. One component, however, to any successful design is flexibility. As Melvin Conway says,

“Because the design which occurs first is almost never the best possible, the prevailing system concept may need to change. Therefore, flexibility of organization is important to effective design.”

Before looking at possible team design structures, let’s first consider a few more principles to guide good design.

Principles to Guide Good Design

In her book A Guide to Organization Design, Naomi Stanford writes that organizing an enterprise “…needs to include the culture, group processes, leadership, measurement and stakeholder engagement if it is to result in an organization that is aligned in a way that will achieve the organization’s strategic goals.”

She specifically lays out these principles to guide good design.

- Design for Business Reasons

Lay out the business case for the design, and whenever possible include the anticipated growth or ROI. An organization needn’t be redesigned for innovative technology or to suit a senior executive’s preferences when these changes don’t have an underlying business reason.

- Design a Team in Light of the Entire Organization

An effective team structure doesn’t operate as its own fiefdom within the company. Rather, it considers the organization as a whole, carefully considering its communication networks and dependencies on other departments.

- Design for the Future

As much as we want to fix things for right now, it’s necessary to look ahead and incorporate anticipated changes into the design.

- Allocate Specific Resources to Design

As discussed, successful output hinges on good design. Conversely, a poor design may well spell failure even to highly skilled teams. And so a high-functioning organization dedicates resources, possibly even an entire team, into researching good design.

- Design for Continual Transformation.

More than likely, you’re never “there” with design. It’s something to continually monitor and tinker with.

Bearing these principles in mind, let’s consider various organization structures, and the benefits and downsides of each.

1. Centralized Organization

Centralized design is a structure where key decisions, plans, strategies and budgets are established by a single leadership or team. A centralized organization may have multi-disciplinary teams, where one manager oversees many disciplines. In a marketing organization, for example, both a designer and a marketer would report to the head of product design.

The Benefits

Overall costs tend to be lower in a centralized organization. Things like procurement are centralized, so there’s no paying double for the same services in various departments. Additionally, there’s a standardization across the entire organization. Each team inherits the best practices of another team, and there’s a consistent culture throughout.

Centralized organizations allow a company to innovate and grow quickly, and so it’s popular in small developing companies.

The Downsides

Centralized organization can slow processes and complicate communication systems. People from different departments who work on the same assignment cannot communicate and make decisions directly, but must instead correspond through several channels.

Example

Apple is a well-known organization that utilizes a centralized organization structure. Both historically and currently, the CEO of Apple makes decisions for the entire company. Apple benefits from this centralized organization by having a consistent culture and shared core values throughout the entire company.

An organization might adopt a centralized organization if it’s either poised for growth or needs to streamline processes and cut costs.

2. Decentralized Organization

In a decentralized organization, the same key functions of decision making, budgeting, strategizing and planning are distributed to many people across several departments. In a marketing company, a decentralized organization divides teams into distinct departments such as content, research and design.

Team members report directly to the manager within his or her discipline. Designers report to design managers, researchers to research managers, and so on.

The Benefits

This structure works well in an organization that has many different types of products or services, or that serves many different regions. It fosters innovation, as more people are empowered to make decisions, and allows for easy communication due to its small teams. It’s easier to recruit talent because there’s so much possibility for growth within the company.

The Downsides

In a decentralized organization, processes aren’t streamlined, and so costs tend to be higher. There’s a lack of cohesion, and an organization may develop a scattered or incoherent culture, and operate more like several fiefdoms rather than one large company.

Examples

Netflix is a company with a decentralized structure. In his book No Rules Rules, founder and CEO Reed Hastings explains how he’s built a culture that has eliminated most controls and empowers individuals to make decisions. This structure has allowed Netflix to expand worldwide, and create content for specific regions.

Johnson and Johnson is also notable for its decentralized structure that has allowed it to develop a wide range of bestselling products.

3. Structure for Anticipated Demand

This structure considers the demand for a product or service, and structures the organization accordingly. For example, in a financial services company, leadership first considers the skill level required for the markets it plans to serve. A member with good interpersonal skills might handle high-level clients, while the new employees would be assigned the “C” or “D” clients. Someone who’s experienced but doesn’t have great communication skills would be a team leader.

The Benefits

This structure aligns the right skills with the correct services. It eases the hiring process, as human resources knows the precise level of skill required from recruits.

It also considers capacity right from the start. The leadership understands where and how to leverage the company when it wants to modify services, and who needs additional training.

The Downsides

In this structure, an individual may feel locked into a role. As this design determines demand in advance, it’s difficult for an individual to move up within the organization. Additionally, there’s little crossover or sharing of tasks.

Example

Financial services organizations such as Fidelity structure its organization to meet anticipated demand. It’s also utilized in food service organizations looking to serve a specific clientele.

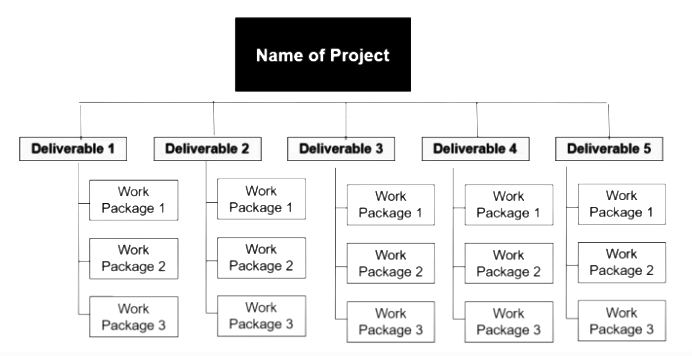

4. Stream Aligned Teams

These next two team structures are taken from Matthew Skelton’s book, Team Topologies.

This first is the stream aligned team. This is a small autonomous team where members independently plan, build, refine, adjust and deliver a product. As the name suggests, the steam aligned team is designed for flow. It provides continuous delivery, and pivots and adjusts based on team and client feedback.

The Benefits

A stream aligned team demonstrates a huge capacity for growth and development. When the same members have worked together for a while, both the roles and collaborative systems are tweaked for maximum potential.

The Downsides

The autonomous nature of these teams means it may operate in isolation, separate from the rest of the organization. It’s resistant to interference from upper management. As it prefers to generate its own schedule, it’s difficult for a stream aligned team to meet externally imposed deadlines.

Example

This is the quintessential agile team. Many software teams designing websites and new applications utilize the stream aligned structure.

5. Enabling Teams

An enabling team isn’t driven by a client or a product design. Rather, it’s expressly dedicated to research, experimentation and innovation.

The Benefits

Enabling teams allow for innovation and growth. It looks at the current processes within the organization and seeks to improve them. It also considers the future trends and needs of the market, and brainstorms products and aligns services to meet them.

The Downsides

Although an enabling team can lead to huge business growth, it uses resources without immediately adding business value. It’s only viable within an organization with plenty of extra time, money, and labor.

Example

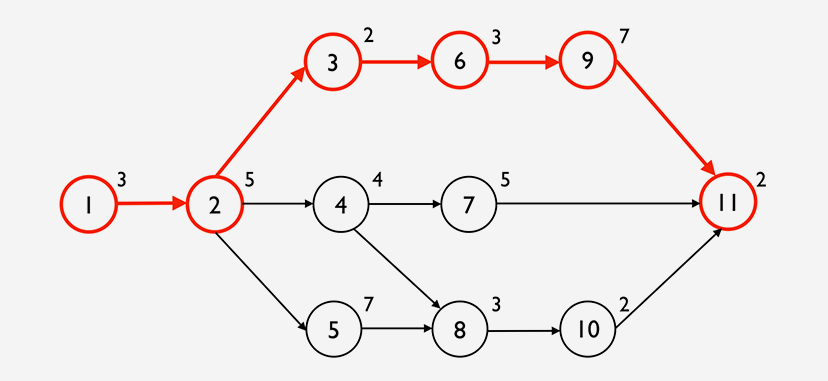

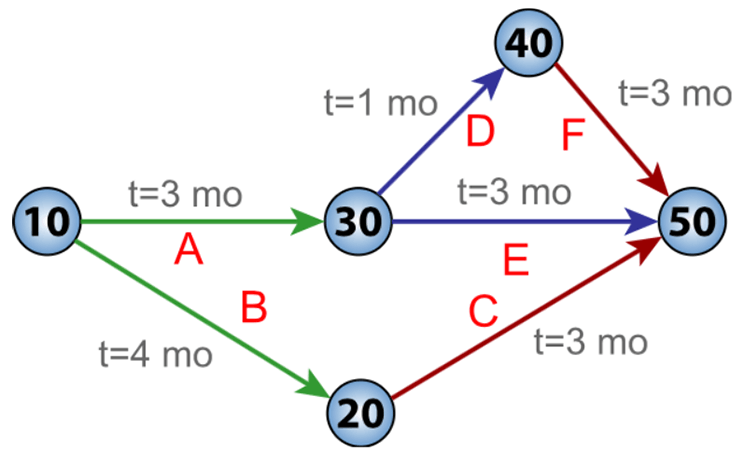

Internal think tanks represent enabling teams. For example, an enabling team within the company DuPont developed what’s come to be known as the critical path method in the 1950s, a concept widely adopted by project managers today.

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it provides some basic guidelines around how to structure a team.

Conway’s two cents are once again worth considering here as a guideline for any structure: “Each individual must have at most one superior and at most approximately seven subordinates.” Another key consideration is the interaction patterns within the team.

Four Interaction Modes of a Team

In order to determine the right team structure, it’s necessary to consider how the team members interact. Most teams don’t function like the quintessential stream-aligned team, where roles oftentimes overlap and team members can swarm around one task. Here are a few possible interaction modes offered by Matthew Skelton and agile coach Cara Leon.

1. Collaboration

This is the interaction mode where everyone on the team possesses a similar set of skills, and can swarm around a work item and push it through the workflow.

2. Facilitating

In this collaboration mode, one unit of the team enables the next. It’s demonstrated in a manufacturing assembly line, where one person completes his or her portion of a project before passing it on. As previously discussed, these team members do not work in silos, but communicate with each other in order to bring the project to completion.

3. Service

In this mode, a team reaches outside itself for a tool or a service. For example, a team may hire a virtual assistant to assist with administrative tasks. Or an IT department may use the servers of another organization.

4. Consult Not to Own

In this collaboration structure, one team supports another in an effort that will ultimately be the possession of the other team.

And this summarizes some common communication modes for a team. As stated before, determining the right solution means stepping away from the “what” of the project or process and looking at it in broad overview.

Now let’s look at some tools and tips to help facilitate an effective team.

Tips and Tools for Building a High-Functioning Team

Building a team is as much about the structure of an organization as it is about skills and leadership. Here are some tools and strategies to facilitate a high-functioning team.

Manage Capacity

Capacity may seem like it has nothing to do with an effective team, while in fact, it’s an essential component to one.

Capacity management is a data driven discipline that collects and analyzes data, then creates procedures and systems based on this analysis. The objective of capacity management is to identify where to improve an organization and how to change current processes to increase value and output.

It means, for example, understanding how many additional clients a service organization can take on for each employee it hires. Within the food service industry, capacity management considers things like how many meals a restaurant can serve during lunch hour, given its current space and staff.

Capacity management makes it clear when and where people need to be hired, and helps to get the resource mix right. It builds self-sustaining systems that enable growth.

Use Time Sheets

Although many employees still fill out timesheets, more and more this procedure is falling away.

Time sheets create a self-managed system. When people fill out their own time sheets, it gives them a clear understanding of how they’ve spent their time in a given day. Essentially, it’s a process that allows them to manage themselves. A team runs without constant oversight from a leader, and becomes system dependent.

Increase Employee Engagement

“Every important business outcome lies downstream from the experience and engagement of the people who make the organization go….Success begins and ends with human beings.” Tracy Maylett, EdD and Matthew Wride, JD write in their book, The Employee Experience.

Employee engagement lies at the heart of an effective team. More and more, increasing this engagement means treating employees like stakeholders in the business. People are no longer willing to work for a paycheck or take orders from their boss.

An employee who feels like he is a part of things brings his full self to his role within the team. He’s more likely to stick around for the long-term.

Building employee engagement isn’t a “one and done” process. An organization is never there, really. Rather, it achieves this objective in degrees.

The first step is to look at underlying assumptions around employees. Are they treated like autonomous adults or like “things” the company has acquired?

This gets down to altering the language used around the workplace. Phrases such as “personal time” and “vacation time” imply that an employer gives employees license on how he or she uses her time.

And the second step is about tactics. Pay and benefits, workspace and well-being all play into improving an employee’s experience and increasing his or her engagement.

Use a Pull (Not Push) System

A pull system is demonstrated by the kanban workflow which sets work-in-process limits.

This system prevents the cognitive overload created by multitasking and conflicting priorities. In a pull system, teams work together to complete tasks in order to move into the next work item. It reduces procrastination and increases efficiency.

Just as in carpentry, when a team leader uses the right tools, it’s so much easier to solidly nail, bolt or fasten a team together for success.

Culture: The Essential Ingredient to Every Team

The functionality of an organization and its culture are closely correlated. A company’s culture makes the difference between a collaborative, innovative team that consistently wows clients, and a bickering team full of infighting that produces mediocre results.

A culture is built and cultivated. It can be deliberately molded. As Lazlo Bock, former executive at Google writes in his book, Work Rules!, “It is within anyone’s grasp to be the founder and culture-creator of their own team, whether you are the first employee or joining a company that has existed for decades.”

The components of work culture include things like purpose, opportunity, appreciation, success, well-being and leadership. Culture is impacted by the systems within an organization that foster work-life balance, as well as its practices to acknowledge and appreciate each employee’s hard work and contributions.

An empowering culture unleashes potential. It gets the best out of each team member. Let’s go over some characteristics of good culture, and explain how to build it within an organization.

Build Psychological Safety

This means creating an open environment where people share opinions and aren’t afraid to take risks. As CEO Reed Hastings reports in No Rules Rules, Netflix goes so far as to censure employees who don’t engage.

“At Netflix, it is tantamount to being disloyal to the company if you fail to speak up when you disagree with a colleague or have feedback that could be helpful. After all, you could help the business—but you are choosing not to.”

As people aren’t afraid to admit to errors, a safe environment catches and fixes mistakes before they become huge problems. It allows a team to seize opportunities, as people are willing to go out on a limb and risk failure.

This openness is created first of all by a leader who shows vulnerability. When a leader admits to mistakes, it creates a space where others can as well.

Show Appreciation

They say that people don’t quit jobs, they quit managers.

But psychologists Gary Chapman & Paul White, authors of The 5 Languages of Appreciation in the Workplace, find that appreciation is so fundamental that employees will quit a job based on this factor alone. Even in a position where the pay and benefits are great, an employee will move onto other pastures if she doesn’t feel appreciated.

Showing appreciation isn’t so simple as saying thank you. It can mean spending time with employees, getting to know them as individuals, providing bonuses and incentives and acknowledging individual contributions to successful projects and endeavors.

Communicate Transparently

Without vigilance, it’s easy for a workplace to devolve into an environment where key information is shared via gossip channels or in games of telephone where the message becomes garbled and misunderstood.

A transparent organization makes a practice of providing regular, dependable communication. In a remote team, this means selecting effective tools and ensuring that everyone checks in and utilizes the tools regularly.

This simple communication structure impacts the team’s collaborative efforts, and ultimately its output.

Keep the Eye on the Ball, Not on Individuals

The team goal is to achieve its objective. Staying focused on this prevents the development of a blame culture where individuals are singled out for mistakes, and which ultimately results in a mistrustful and unmotivated team. Rather it keeps everyone energized on the goal.

These guidelines help to create a friendly, open culture, where people want to speak to each other and engage.

The Ideal Team Member

We’ve all worked with the downer, the slacker, the jerk, the person who hides within a team and works at 30% capacity. And unfortunately, even the best team structure cannot remedy the negative impact this has on a team.

According to Patrick Lencioni, author of the Ideal Team Player, every team member needs to be hungry, humble and smart.

“During the past twenty years of working with leaders and their teams, I’ve seen time and again that when a team member lacks one or more of these three virtues, the process of building a cohesive team is much more difficult than it should be, and in some cases, impossible.”

In order to build a team with these characteristics, it’s necessary to understand just what they mean.

- Hungry: This doesn’t mean someone with a penchant for snacks. Rather, it means he or she is self motivated, and driven to learn, grow and succeed.

- Humble: Even the most skilled team member appreciates that everyone has something to contribute. Listening to other perspectives is key to creating synergy.

- Smart: This isn’t intelligence, skill, or book smarts. Rather, the “smartness” Lencioni refers to is emotional intelligence. It’s someone who “gets” different kinds of people and collaborates well with others.

When a team is composed of people with these qualities, and it has a good design to boot, it can do nothing but succeed.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, there isn’t a step-by-step guide to building an effective team. Nor is there one right team structure. The right design structure depends on the team’s objective, its resources, and its collaboration modes.

Team structure determines the team’s output. And so every organization puts just as much time into its design as it does into production.

A team structure may be centralized, decentralized, or fall somewhere in between. One guiding principle for any design is to create a communication system that’s as simple as possible. Another is flexibility. This way, it’s possible to both plan a structure then monitor and tweak it later.

If you’re building a remote team, consider signing up for Teamly. Our sophisticated project management platform is just the tool you need to establish the simple communication channels necessary to foster a productive team.